Welcome! I am Professor of International Affairs at the School of Public and International Affairs, University of Georgia. I received my Ph.D. in political science from University of California, Berkeley in December 2012. Before Berkeley, I studied at Peking University, China and National University of Singapore. My research interests are social activism, media politics, political participation, and democratization. My area focus is China.

Welcome! I am Professor of International Affairs at the School of Public and International Affairs, University of Georgia. I received my Ph.D. in political science from University of California, Berkeley in December 2012. Before Berkeley, I studied at Peking University, China and National University of Singapore. My research interests are social activism, media politics, political participation, and democratization. My area focus is China.

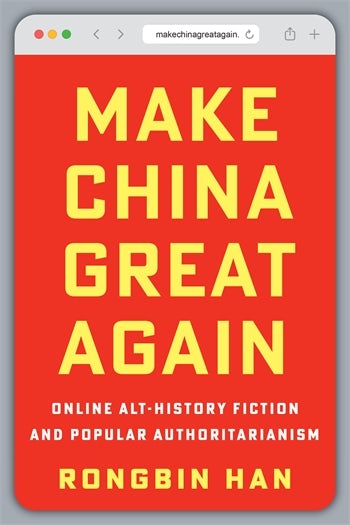

Get 20% off with code CUP20 when you order my new book Make China Great Again: Online Alt-History Fiction and Popular Authoritarianism from the publisher (cup.columbia.edu). To get the book from Amazon, click here. For more details, click here.